Most of us who are engaged in development or use of open-source software have one reason or another to do it. The question of "Why open-source?" is something we should all reflect upon once, since we should be well prepared to answer the same question confidently in the future.

It was inspiring to see sessions dedicated to open-source in AGU 2017, and even more exciting to hear mentions of Python usage in talks here and there. I really encourage you to have a look at this informal session titled Open-Source Software in the Geosciences. The content of the session applies to all open-source development in sciences in general, although it was intended to be focussed on geosciences.

Since the video is rather long, I have summarized the gist of the talk below. The following questions were asked to the panel.

1. What considerations went into the decision of making a software openly available?

Because there were no alternative (both open or closed) for a specific new scientific method.

Because it is the right thing to do, since:

- Journals require through terms and condition for the author to make results completely reproducible, a condition rarely enforced.

- Science conducted using the public's tax money, rightfully belongs to the public.

1.1. ... decision of not making a software openly available?

- Slobbily written open-source code can flood your email inbox with queries in the future. Counterpoint: bad code is much better than no code at all.

- Current academic setup does not consider software development as a metric for career advancement.

2. Has making FOSS affected your career?

- With community use, comes fame, and through fame one gets more citations (caution, in the long term). Documentation and tests are very important to promote community adoption.

- A novel method implemented in an open source software can make it a lot more attractive to the community.

2.1. Means to promote your code

- Through talks, social and professional contacts, Github (and similar).

- Should be citeable. i.e. include a BibTeX in the README. Options include Earthcube (to publish workflows), JORS, JOSS (open-access journals dedicated to open-source software).

3. Community impact

- Colleagues inspired to use software, provided if they are open-minded and the supervisors are encouraging.

- Adoption of the software is typically slow in the first few years, but picks up gradually - so stay strong!

- Python is popular these days. Why? The possibility to integrate workflow, including I/O and plotting.

- Could become a benchmark code, for even validating commercial codes!

- Will license pose a barrier for use of the code? A general thumbrule could be as follows. Intended for industry use or to function as a library: choose GPL v2, BSD or MIT. Intended only for academic and non-profit applications, and to ensure pull-requests: choose GPL v3.

- Learning version control (mercurial or git) can be a barrier to start with.

- Grad students go for open-source software just to get the work done. In the long run however they may contribute back. Encourage them, even if they don't fully understand how to keep a consistent code style, and the importance of comments and documentations. In short, keep the code review process constructive. It is a good idea to maintain a one page CODE_OF_CONDUCT text file.

- Some organisations which are promoting open-science: Software Carpentry and Mozilla Science

4. Has your perception changed through making FOSS?

- Version control offers sense of security in case your laptop gets stolen or broken.

- Unittests offer confidence in your results, and ensures less bugs.

- Continuous testing ensures others will not break your unittests, thus existing functionality.

- Feel-good effect to have become a better scientist? Perhaps.

5. Any regrets?

- Poor choice of license in the beginning. Hard to change in the long run.

- Always ask your boss before you release the code.

- Email queries about a piece of code you wrote long back, that you have no idea about now. No docs!

- Lonely in the absence of community.

6. Future of FOSS development

- More professional, disciplined codes.

- Web services - codes deployed as a service opens up the possibility for a layman to make a simulation even through one's smart phone. Right now it is restricted to computationally non-intensive calculations (for eg. Jupyter notebooks, JupyterHub). An example of this is the JHU turbulence database.

- Research funds and resources allocated to code development, not just for buying laboratory apparatus and commercial software.

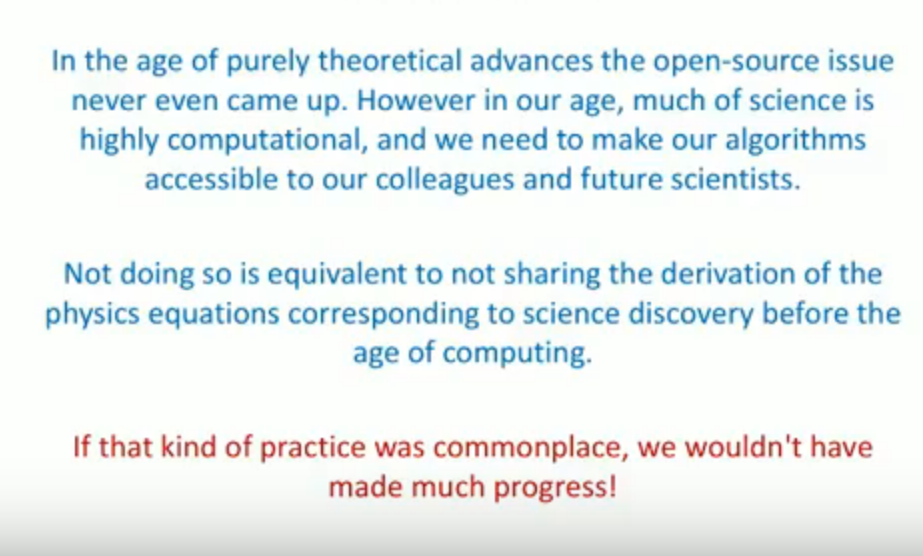

An inspiring quote to end with: